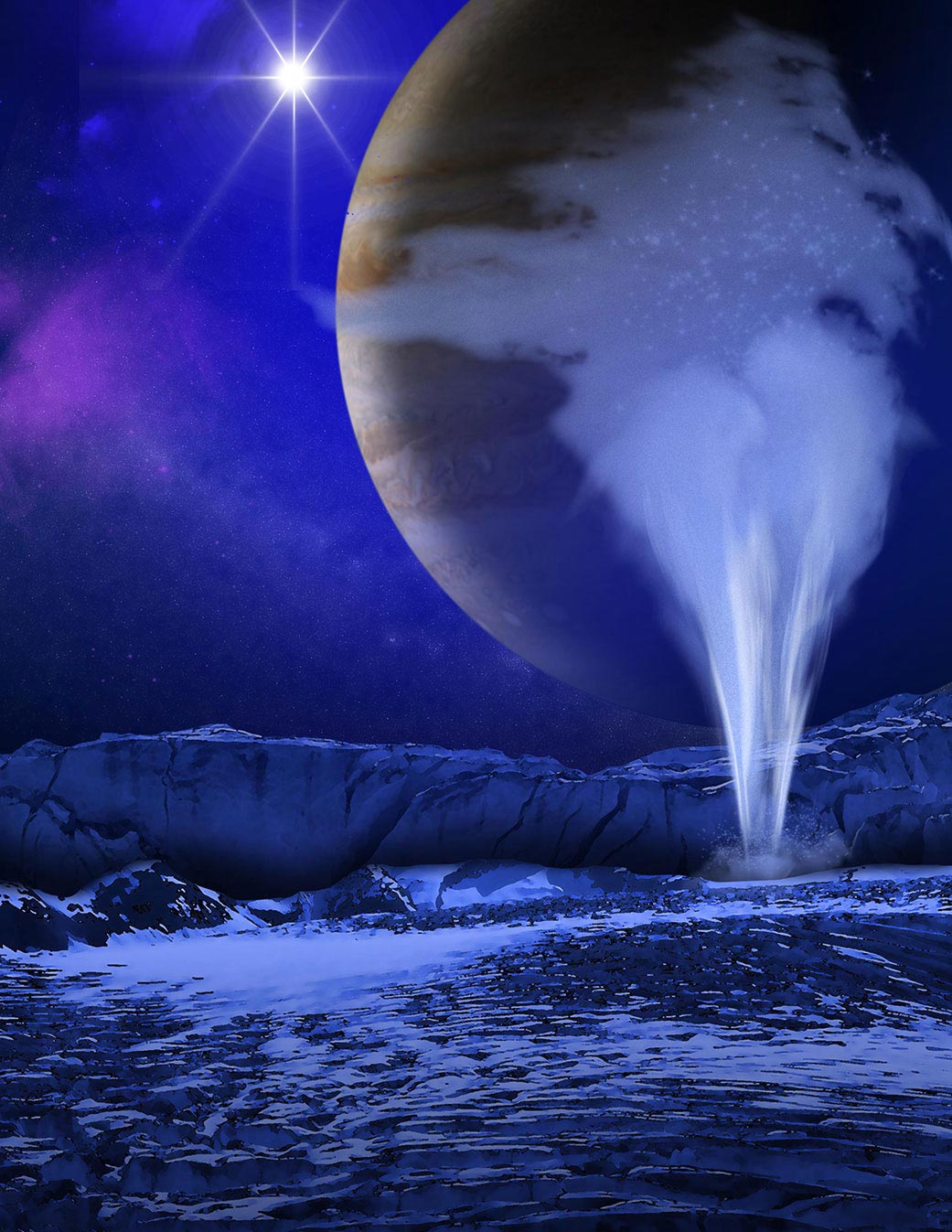

Esta ilustración muestra una columna de vapor de agua que podría emitirse desde la superficie congelada de la luna Europa de Júpiter. Una nueva investigación arroja luz sobre qué penachos, si es que hay alguno, podrían revelar sobre los lagos que pueden estar dentro de la corteza lunar. Crédito: NASA/ESA/K. Retherford / SWRI

Nuevas investigaciones científicas hacen suposiciones de que[{» attribute=»»>NASA’s Europa Clipper can test: Any plumes or volcanic activity at the Jovian moon’s surface are caused by shallow lakes in its icy crust.

Subsurface bodies of water in our outer solar system are some of the most important targets in the search for life beyond Earth. That’s why NASA is sending the Europa Clipper spacecraft to Jupiter’s moon Europa: There is strong evidence that under a thick crust of ice, the moon harbors a global ocean that could potentially be habitable.

Europa is considered one of the most promising places in our solar system to find present-day environments suitable for some form of life beyond Earth.

Scientists are almost certain that a salty-water ocean thought to contain twice as much water as Earth’s oceans combined is hidden beneath the icy surface of Europa. And like Earth, Europa is thought to also contain a rocky mantle and iron core.

Very strong evidence suggests Europa’s ocean is in contact with rock. This is significant because life as we know it requires three essential “ingredients”: liquid water, an energy source, and organic compounds to use as the building blocks for biological processes.

Europa could have all three of these ingredients. And there would have been plenty of time for life to begin and evolve there, as its ocean may have existed for the whole age of the solar system.

However, scientists think the ocean isn’t the only water on Europa. Based on observations from NASA’s Galileo orbiter, they believe the moon’s icy shell could contain salty liquid reservoirs – some of them close to the surface of the ice and some many miles below.

The more scientists understand about the water that Europa may be holding, the better chance they will know where to look for it when NASA sends Europa Clipper in 2024 to conduct a detailed investigation. The spacecraft will orbit Jupiter and use its suite of sophisticated instruments to gather science data as it flies by the moon about 50 times.

Now, research is helping scientists better understand what the subsurface lakes in Europa may look like and how they behave. A key finding in a paper published recently in Planetary Science Journal supports the longstanding idea that water could potentially erupt above the surface of Europa either as plumes of vapor or as cryovolcanic activity (think: flowing, slushy ice rather than molten lava).

The computer modeling in the paper goes further, showing that if there are eruptions on Europa, they likely come from shallow, wide lakes embedded in the ice and not from the global ocean far below.

“We demonstrated that plumes or cryolava flows could mean there are shallow liquid reservoirs below, which Europa Clipper would be able to detect,” said Elodie Lesage, lead author of the research and Europa scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California. “Our results give new insights into how deep the water might be that’s driving surface activity, including plumes. And the water should be shallow enough that it can be detected by multiple Europa Clipper instruments.”

This color view of Jupiter’s moon Europa was captured by NASA’s Galileo spacecraft in the late 1990s. Scientists are studying processes that affect the moon’s surface as they prepare to explore the icy body. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SETI Institute

Different Depths, Different Ice

Lesage’s computer modeling lays out a blueprint for what scientists might find inside the ice if they were to observe eruptions at the surface. According to her models, they likely would detect reservoirs relatively close to the surface, in the upper 2.5 to 5 miles (4 to 8 kilometers) of the crust, where the ice is coldest and most brittle.

That’s because the subsurface ice there doesn’t allow for expansion: As the pockets of water freeze and expand, they could break the surrounding ice and trigger eruptions, much like a can of soda in a freezer explodes. And pockets of water that do burst through would likely be wide and flat like pancakes.

Reservoirs deeper in the ice layer – with floors more than 5 miles (8 kilometers) below the crust – would push against warmer ice surrounding them as they expand. That ice is soft enough to act as a cushion, absorbing the pressure rather than bursting. Rather than acting like a can of soda, these pockets of water would behave more like a liquid-filled balloon, where the balloon simply stretches as the liquid within it freezes and expands.

Sensing Firsthand

Scientists on the Europa Clipper mission can use this research when the spacecraft arrives at Europa in 2030. For example, the radar instrument – called Radar for Europa Assessment and Sounding: Ocean to Near-surface (REASON) – is one of the key instruments that will be used to look for water pockets in the ice.

“The new work shows that water bodies in the shallow subsurface could be unstable if stresses exceed the strength of the ice and could be associated with plumes rising above the surface,” said Don Blankenship, of the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics in Austin, Texas, who leads the radar instrument team. “That means REASON could be able to see water bodies in the same places that you see plumes.”

Europa Clipper will carry other instruments that will be able to test the theories of the new research. The science cameras will be able to make high-resolution color and stereoscopic images of Europa; the thermal emission imager will use an infrared camera to map Europa’s temperatures and find clues about geologic activity – including cryovolcanism. If plumes are erupting, they could be observable by the ultraviolet spectrograph, the instrument that analyzes ultraviolet light.

Reference: “Simulation of Freezing Cryomagma Reservoirs in Viscoelastic Ice Shells” by Elodie Lesage, Hélène Massol, Samuel M. Howell and Frédéric Schmidt, 21 July 2022, Planetary Science Journal.

DOI: 10.3847/PSJ/ac75bf

More About the Mission

Missions such as Europa Clipper contribute to the field of astrobiology. This is an interdisciplinary research field that studies the conditions of distant worlds that could harbor life as we know it. Although Europa Clipper is not a life-detection mission, it will conduct a detailed exploration of Europa and investigate whether the icy moon, with its subsurface ocean, has the capability to support life. Understanding Europa’s habitability will help scientists better understand how life developed on Earth and the potential for finding life beyond our planet.

Managed by the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena, California, JPL leads the development of the Europa Clipper mission in partnership with APL for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. APL designed the main spacecraft body in collaboration with JPL and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. The Planetary Missions Program Office at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, executes program management of the Europa Clipper mission.

«Maven de internet exasperantemente humilde. Comunicadora. Fanático dedicado al tocino.»

También te puede interesar

-

Una investigación sugiere que una dieta tradicional japonesa puede beneficiar la salud cerebral de las mujeres

-

Investigadores de la Universidad de Utah recolectan muestras para mapear la propagación de la fiebre del valle a través de esporas en la tierra

-

La NASA confirma que el misterioso objeto que se estrelló contra el tejado de una casa en Florida procedía de la estación espacial

-

Los científicos identifican tres nuevas especies de canguros antiguos, uno de los cuales medía más de 2 metros de altura

-

Este extraño gusano tiene una 'visión excepcional' y los científicos no saben por qué: ScienceAlert